Back in 1906, an Italian engineer turned economist named Vilfredo Pareto made a startling discovery: 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. He studied land ownership patterns in a number of other countries and found that the same ratio applied. He also found that the ratio seemed to apply in other contexts: for example, 20% of the pea pods in his garden produced 80% of the peas. In the 1940s, an American engineer named Joseph Juran noticed that 80% of the quality problems in industrial mass-production systems seemed to come from 20% of the possible causes. He then stumbled on the work of Pareto and christened the 80/20 split the Pareto Principle in his honour.

Naughton’s account is a good summary. But Google “Pareto Principle” and you will find variations on its origins. In the interviews from “An Immigrant’s Gift,” Dr. Juran himself discussed how he discovered and named the Pareto Principle:

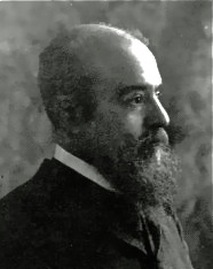

JOSEPH JURAN: Pareto was a real person. He was an Italian, an economist, an engineer. And one of the things he once did was to study the distribution of wealth in Italy. Well, of course, he found few families had most of the money and the rest of them didn't have much. Vital few, useful many -- if you want to use that term. That was my term, not his.

I first learned about him when I was visiting General Motors Corporation. (Someone) showed me something that he didn't show to very many visitors. He showed me a study he had made of the distribution of salaries in General Motors. And he had . . . found Pareto, and the logarithmic curve Pareto had developed fitted the General Motors thing. And we discussed that. I checked his mathematics. . . .We couldn't do anything like that in Western Electric. But the name "Pareto" I latched onto. Put that in my memory in case I ever needed it.

Well, soon after that I did need it . . . When I was (working on) the Quality Control Handbook, I needed a shorthand name for a phenomenon that when you got a lot of different defects of ilk. You produced something and got a lot of things the matter with it. Maybe a hundred different diseases of that product. But, when you look at the frequency of each disease . . . like the mortality tables, a few diseases account for most of the sickness. Well, not only there, you've got absenteeism. A few people account for most of the absences. A few people account for most of the accidents, et cetera.

There's a universal situation there, that in a total amount of effect, a relative few of the causes account for most of the effect. I needed a shorthand name for that. And then I remembered Pareto. Now, he hadn't generalized this principle. He was just studying wealth. But I adopted the name. I wasn't willing to call something like that the Juran Principle. (I am) not structured that way. So, to my knowledge, I'm the first one that generalized that. And that was the birth of the Pareto Principle.

Image of Vilfredo Pareto from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Vilfredo_Pareto.jpg with permission.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed